Liberal Arts Education is Not Only a Western Concept

Teachers in ancient India and China were the first to educate young people to become “well-rounded, responsible” individuals, much like contemporary liberal arts and sciences educators do today, writes Kyaw Moe Tun in a recent issue of Times Higher Education. Kyaw Moe Tun is President of Parami University and Director of the OSUN Liberal Arts and Sciences Collaborative.

By Kyaw Moe Tun

US-style liberal arts education is dismissed in many parts of the world as a form of soft American imperialism. When I was trying to establish a liberal arts university in Burma/Myanmar, for instance, nationalists and even some conservatives noted that I was educated in the US and branded me a Western puppet. My response was that I had not fallen in love with the American model of higher education. I had fallen in love with an educational philosophy that is the foundation not only of a modern liberal arts education but also of many ancient educational systems of the East.

The English term “liberal arts” is derived from the Latin artes liberales, but ancient Rome is not the origin of this educational approach. Nor was it invented by the Romans’ cultural progenitors, the ancient Greeks. The primary philosophy behind the Greeks’ liberal arts education was simple and noble: to liberate the mind and to instill comprehensive cognitive skills and habits necessary to participate in civic duties. In that sense, artes liberales is best translated as “skills/subjects for a liberated/free person.” Students were required to study both the quadrivium arts (arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy) and trivium arts (grammar, rhetoric and logic).

Early American educators adopted a similar philosophy, and US bachelor degree programs still attempt to offer a broad-based understanding of how the world generally works. Every student is generally required to take a certain minimum number of courses in different disciplines, including arts, humanities, social sciences and sciences, regardless of their desired major.

But different American colleges and universities interpret the liberal arts education slightly differently. For instance, my alma mater, Bard College, offers a combination of seminar courses in great literary books and distributional requirements in various disciplines. Other institutions, such as SUNY Empire State College, understand a liberal arts education as one that focuses on traditional “academic” fields, as opposed to professional and vocational majors such as accounting, business administration and technology. Still others, such as the New School, give students the freedom to consult with their faculty to develop study plans based on their interests.

What makes it even more confusing is the fact that a few American universities, such as Southern New Hampshire University, as well as non-American universities (the UK universities of Winchester and Sussex, for example) offer liberal arts as majors that focus almost exclusively on humanities and the arts.

Still, the similarity of all these approaches to certain ancient aspirations to create well-rounded and responsible citizens are striking. One example is the ancient Chinese higher education system, beginning in the Zhou dynasty (1046 BCE–256 BCE). Developed by Confucius, this involved learning the “six arts” of “rites,” music, archery, charioteering, calligraphy and mathematics. Of course, these subjects were relevant to those times, as much as the subjects that were part of the quadrivium and trivium arts were relevant to the time of the ancient Greeks. But the broadly focused philosophy is similar. Those who excelled in these six arts were regarded to have achieved a state of perfection.

This style of Chinese liberal arts education is something I have been familiar with since I was young. As an ethnically Chinese Burmese citizen, I grew up watching Chinese historical TV series with my parents, in which young men (women, of course, were excluded from learning) were depicted learning the six arts under their “masters.” My father would explain that you had to be well-rounded to enter the ancient Chinese civil service and become an impactful leader.

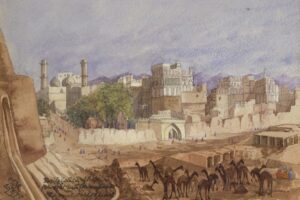

Another example is ancient education on the Indian subcontinent. Takshashila (Taxila), a UNESCO world heritage site in modern-day Pakistan, is now considered one of the first universities in the world, if not the earliest. Nalanda monastic university was developed during the Gupta Empire (early 4th century to late 6th century) and is considered to be the world’s first planned residential university. The educational philosophy ingrained in such institutions, under the Vedic influence, was to develop “whole” individuals, with the emphasis on self-reliance, formation of character and the mental, physical and spiritual development of individuals, with a special focus on civic duties.

The curriculum was comprehensive, involving four Vedas: Vedic hymns, Vedic mantras, Vedic melodies, and Vedic rites); four Upa Vedas: medicine, weaponry, performing arts, and architecture; six Vedangas: phonetics, rituals, grammar, philology, metrics, and astronomy; and four Upangas: history, justice, critical investigation, and ethics. When I was a student in public basic education schools in Yangon, I learned about the importance of these 18 acquirements from a learned man in Buddhist jataka stories, and my middle school teachers praised this approach to becoming well-rounded, versatile individuals.

The whole world needs graduates who are not just narrowly focused professionals. In that sense, it is encouraging that the Indian government appears to have recognized that in its New Education Policy, which emphasizes a liberal definition of the arts that goes back to the idea of the 64 kalas, or arts, canonized in India’s ancient books, which included engineering, medicine, and mathematics.

As India appears to have recognized, it is not only inaccurate to view the education of young people as whole individuals as a Western imposition, but it is also deeply counterproductive.